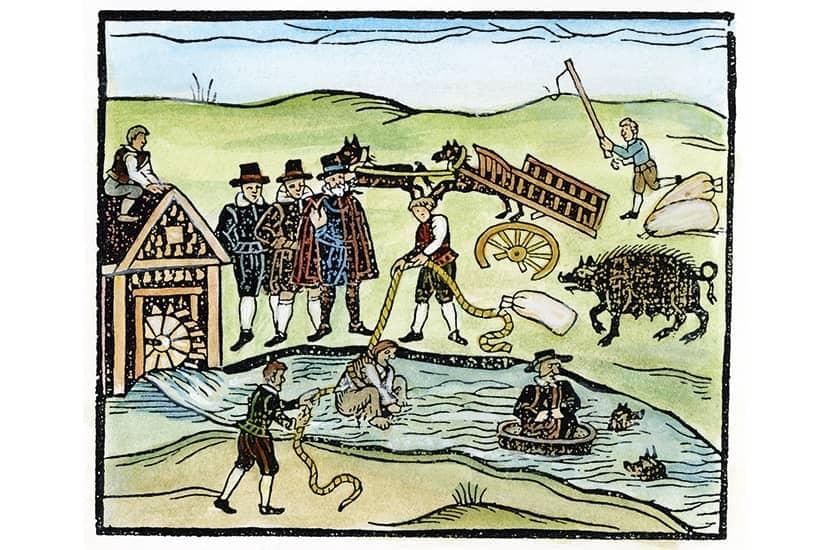

In the three centuries between 1450 and 1750 in Europe it is estimated that up to 100,000 women were burned, hanged, drowned or put to death in other ingenious ways on suspicion of being witches. John Callow’s thoroughly researched book tells the story of three such women, the last judicial victims in England of what has been dubbed ‘the great European witch craze’.

Craze is an appropriate word for a phenomenon which spanned a period when the Continent was supposedly emerging from the dark ages of superstition into the sunlight of the Enlightenment. But in the dawning Europe of Kant, Voltaire and Newton a cloud of unreason persisted, of which the Bideford witch trial was a small but significant example.

In 1682, Grace Thomas, the sister-in-law of Thomas Eastchurch, a prosperous businessman in the Devon port of Bideford, was stricken by a mysterious illness. Eastchurch called in expensive physicians who treated Grace with various remedies; but nothing seemed to work and she remained bedbound. Then one day a magpie flew into the house and flapped about before being chased out by two servants.

In the street they spotted a well-known local beggar woman, Temperance Lloyd, lurking in the shadows. They reported this to their master, who made an instant connection between his sister-in-law’s illness, the bird’s brief incursion and the presence of Temperance in the vicinity. On these flimsy grounds Eastchurch accused Temperance of bewitching Grace. He took his case to the constabulary and Temperance was confined in the local lockup. While she was there, others came forward to accuse her of various forms of enchantment, including causing sickness or injury by sympathetic magic. Confronted by the charges, she made a partial confession, blaming a sinister ‘man in black’ who had driven her into league with the Devil.

One accusation led to another in a spreading stain of suspicion, and two more beggar women, Mary Trembles and Susannah Edwards, were drawn into the web. All three were committed for trial at Exeter Assizes and hanged. The evidence against them was chiefly hearsay, though the accused made confessions and tried to blame each other for their ‘crimes’. Callow points out that the case of the Bideford Three was typical of other witch trials of the period and stories of women with extra teats at which imps suckled, dubious confessions of having sex with the Devil, and blame for inexplicable misfortunes being cast on those who were elderly, poor or lived alone. Some had a reputation for being ‘cunning women’, who used herbal remedies and charms to cure diseases or cast spells.

Callow examines in detail the surviving evidence of the Bideford case, while also imaginatively reconstructing events to create a convincing picture of how superstition and belief in sorcery lay just beneath the surface of a mercantile society struggling to be born. I am surprised he doesn’t mention that at the same time as the Bideford trial, England was suffering the fallout of another outbreak of mass paranoia: the Popish Plot.

That fictitious conspiracy also led to the execution of innocents — 22 men who happened to be Catholics — proving that a society which had just suffered the trauma of civil war, plague and the great fire of London was apt to turn on ‘the other’, and wreak vengeance for its ills on unpopular minorities. It is a lesson that perhaps we still need to learn.

Callow manages to draw a more optimistic conclusion from the trials he describes in such readable detail. For him the Bideford witches were not only sacrificial victims of society’s savagery but also representatives of the stubborn survival of the better angels of our nature. He links the witches — who may indeed have practiced elements of Wicca paganism — with modern feminists and the Greenham Common women who challenged phallic patriarchy and invoked the witches as they did so.

In a bright and breezy coda, Callow describes the successful campaign in 2019 to unveil a commemorative plaque to the witches in Exeter’s Rougemont Gardens, the site of their trial. He writes:

‘If the lives of the Bideford witches were uniformly degraded, miserable and hopeless, then their legacy has been anything but. Their names have been reclaimed through celebration, creativity and activism, entertaining a new generation for whom witchcraft has positive connotations.’

In the age of Harry Potter, who’s to say he’s wrong?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.