“What exactly is it you do?” asked a bamboozled King Alfonso XIII of Spain upon meeting Sergei Diaghilev at a reception in Madrid, while the Great War raged on in Europe. “Your Majesty, I am like you,” came the impresario’s quick-witted reply. “I don’t work, I do nothing. But I am indispensable.” At first glance, the Russian expatriate’s estimation of his own worth may seem theatrically grandiose, but as the dance critic Rupert Christiansen shows in Diaghilev’s Empire, his new history of the Ballets Russes and their buccaneering onlie begetter, “indispensable” was really no overstatement.

Now, 150 years after Diaghilev’s birth, the story of the Ballets Russes, its temperamental director and the wild program of scandals and intrigues that played out both on stage and off is of course well known. But where Christiansen’s book comes into its own is in its description of the radical and lasting changes that Diaghilev brought to bear on the art form — changes made all the more striking by some extended, insightful considerations of what came before and after the fact. Part biography, part history of ballet in the twentieth century, the book looks at how the larger-than-life impresario was able to take what was at the end of the nineteenth century the “childish business” of ballet and not only drag it, often through sheer force of will, into artistic maturity, but also establish it as “a crucial piece in the jigsaw of western culture.”

Strange though it may seem, ballet was not the obvious choice for the young Diaghilev. His first experience of it, in Vienna, had left him cold. But he was drawn to artistic circles and was convinced that his talents could be put to good use there. “First of all I am a great charlatan,” he confessed to his stepmother in a moment of winning candor. “Second I’m a great charmer; third I’ve great nerve; fourth I’m a man with a great deal of logic and few principles; and fifth I think I lack talent.” Where did all this lead? “I think I’ve found my real calling,” he explained: “Patronage of the arts.”

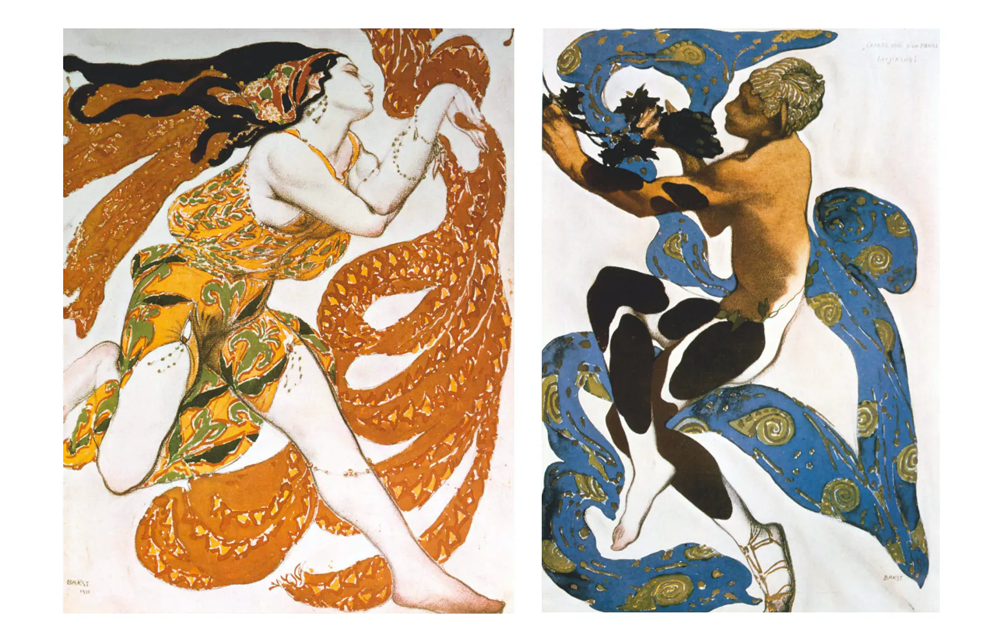

While Diaghilev famously achieved his aim of turning ballet into a Gesamtkunstwerk by commissioning such luminaries as Michel Fokine, Igor Stravinsky, Léon Bakst and Pablo Picasso, he also, as Christiansen highlights, frequently employed other less reputable means. Indeed, he had a knack for buying into rule-breakers “cheap and early,” raising their market value with no little investment of time, patience and subterfuge. When a young Vaslav Nijinsky was fired from the Imperial Ballet in 1911 (his refusal to cover his outrageously revealing tights in a production of Giselle had so shocked the dowager empress as well as several courtiers that it was deemed a case of lèse-majesté), Diaghilev immediately capitalized on it. Dispatching a telegram to his agent in Paris, he ordered him to spread the story: “Appalling scandal. Use publicity.” This was the birth of public outrage as a marketing tool, and from the outset the impresario intended to extract everything he could from it.

Diaghilev’s self-avowed lack of scruples extended well beyond his pursuit of publicity, too, and Christiansen does not shy from the more challenging aspects of his life and legacy as viewed today. Time and again we see the impresario taking young and vulnerable dancers to bed in return for patronage as well as a leg up. His directorial-cum-dictatorial tendencies, as well as his quick temper and supremely fragile sense of amour-propre, led him to sabotage and even to end the careers of several of his own troupe, and are rightly spotlighted here, although thankfully without veering into the heavy-handed or moralistic.

Perhaps one of the less anticipated aspects of book is that Diaghilev’s death in Venice, complete with the dancers Serge Lifar and Boris Kochno brawling over his not quite cold corpse, comes just two-thirds of the way through. In the chapters that follow, the author opts to take a wide-angle view of Diaghilev’s many rivals, survivors and successors, marshaling an impressive range of memoir, private correspondence and journalism to provide a convincing and genuinely illuminating sense of the many fields — ballet, art, literature and film — in which his legacy ebbs and flows today.

While Christiansen, as he explains in his preface, may not have set out to ‘thrill scholars and experts’ with a radical reassessment of Diaghilev’s life, he ultimately achieves something else entirely. Diaghilev’s Empire is a riveting account of a visionary who, for all his many faults, truly did make himself indispensable. Written with sympathy and wit, the book is judiciously researched; but, more crucially, it draws on a lifetime of balletomania, giving readers the benefit of exceptional range. It is also a delicious read into the bargain.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.